Winning a Predictive Maintenance Data Challenge with Engineering Expertise

|

Co-author: Peeyush Pankaj Peeyush Pankaj is an application engineer at MathWorks with a strong Aerospace background and deep domain expertise in vibrations and mechanical systems (engine lubrication circuit design & analysis). In this blog post, he tells us about his experience at the 2025 Prognostics and Health Management Society Conference Data Challenge. |

Shyam Joshi and Reece Teramoto present the team's winning solution at the PHM Society Conference 2025 in Bellevue, WA.

A Real-World Data Challenge

The 2025 PHM Data Challenge asked participants to predict when two components of a commercial jet engine would need maintenance. Using sensor data from four engines across thousands of flights, teams had to create models to estimate how many flights remained before three different maintenance events: High Pressure Turbine (HPT) shop visit, High Pressure Compressor (HPC) shop visit, and HPC water wash. The three maintenance predictions made this a more complex problem than previous PHM data challenges. The dataset was intentionally realistic and messy, with missing sensors, noise, and flights out of order. And predictions that came too late were penalized more heavily. The teams faced a big challenge to generalize well and avoid overfitting the data. This was no simple toy example.Engineering Expertise + MATLAB = Win

This year, MathWorks had two advantages in the data challenge: deep engineering domain expertise and a knowledge of AI and Predictive Maintenance tools in MATLAB. The team was led by Peeyush Pankaj, co-author of this post, whose prior career in aerospace engineering helped him lead the team to interpret degradation patterns, identify practical domain-specific features, and understand realistic engine behavior. Next, Peeyush describes how MathWorks did it.The Solution

Read the full Paper: Maintenance Service Events Prediction Modeling of Aircraft Gas Turbine Engines | Annual Conference of the PHM Society What made this year’s PHM Society Data Challenge particularly interesting was how closely it resembled the messiness of real engine prognostics. We were given only four engines for training, each with multiple failure-linked events that interact with one another the same way they do on a real fleet. The test engines operated in envelopes not seen in training, several sensors were entirely missing, and the individual flight files were shuffled out of sequence. This is very typical of fielded assets: a model must learn from whatever limited history is available and still generalize to engines of the same make and model that operate differently, age differently, and undergo maintenance at different intervals. The challenge captured that reality extremely well.

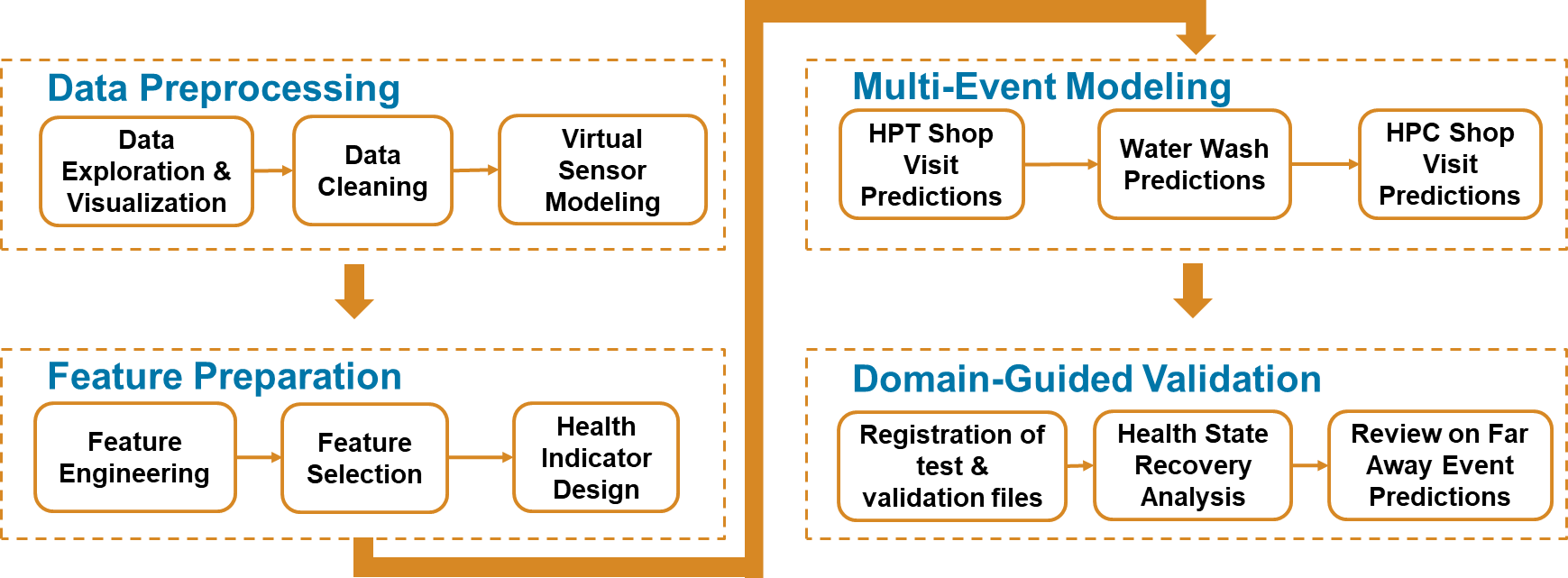

The approach used by the MathWorks team

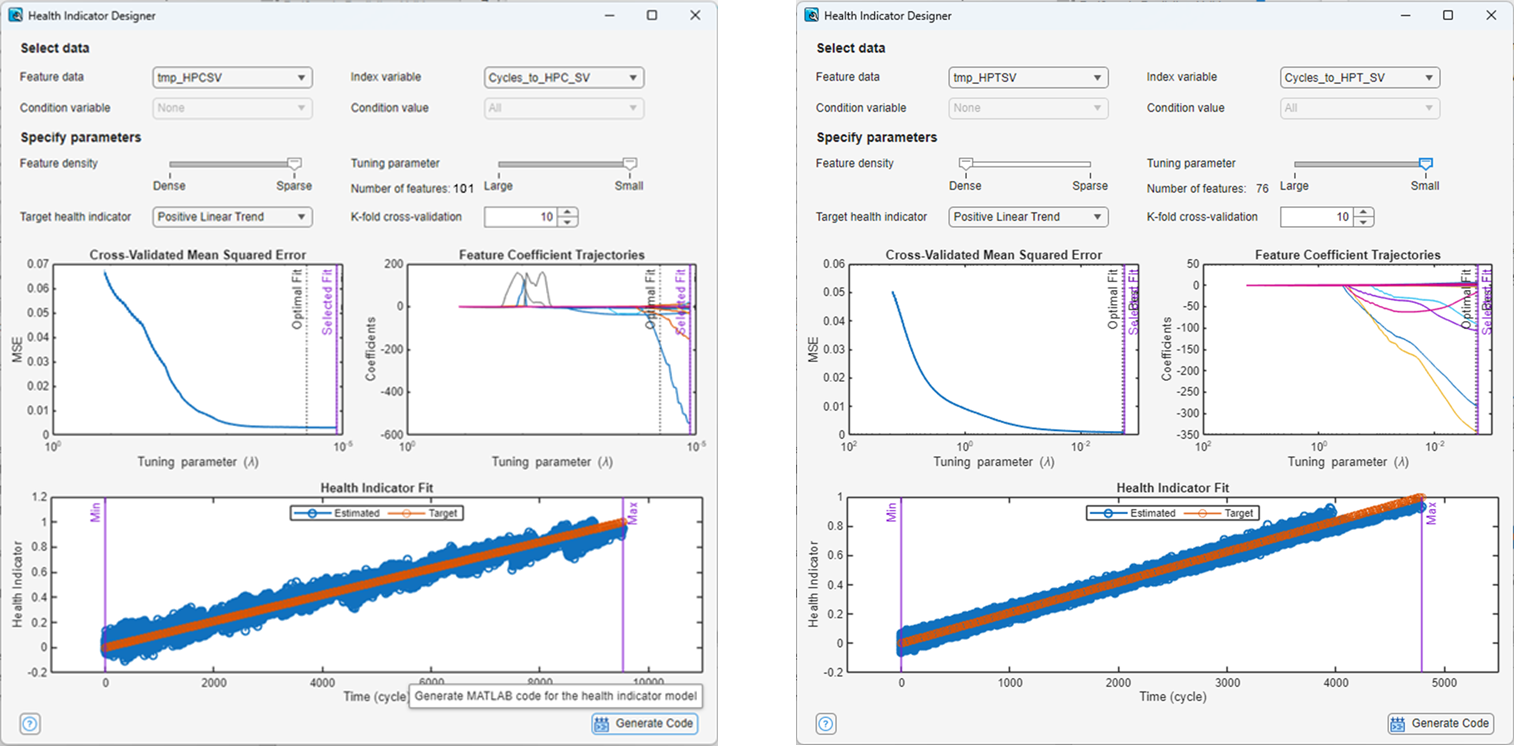

Using Health Indicator Designer to design custom health indicators for HPC and HPT.

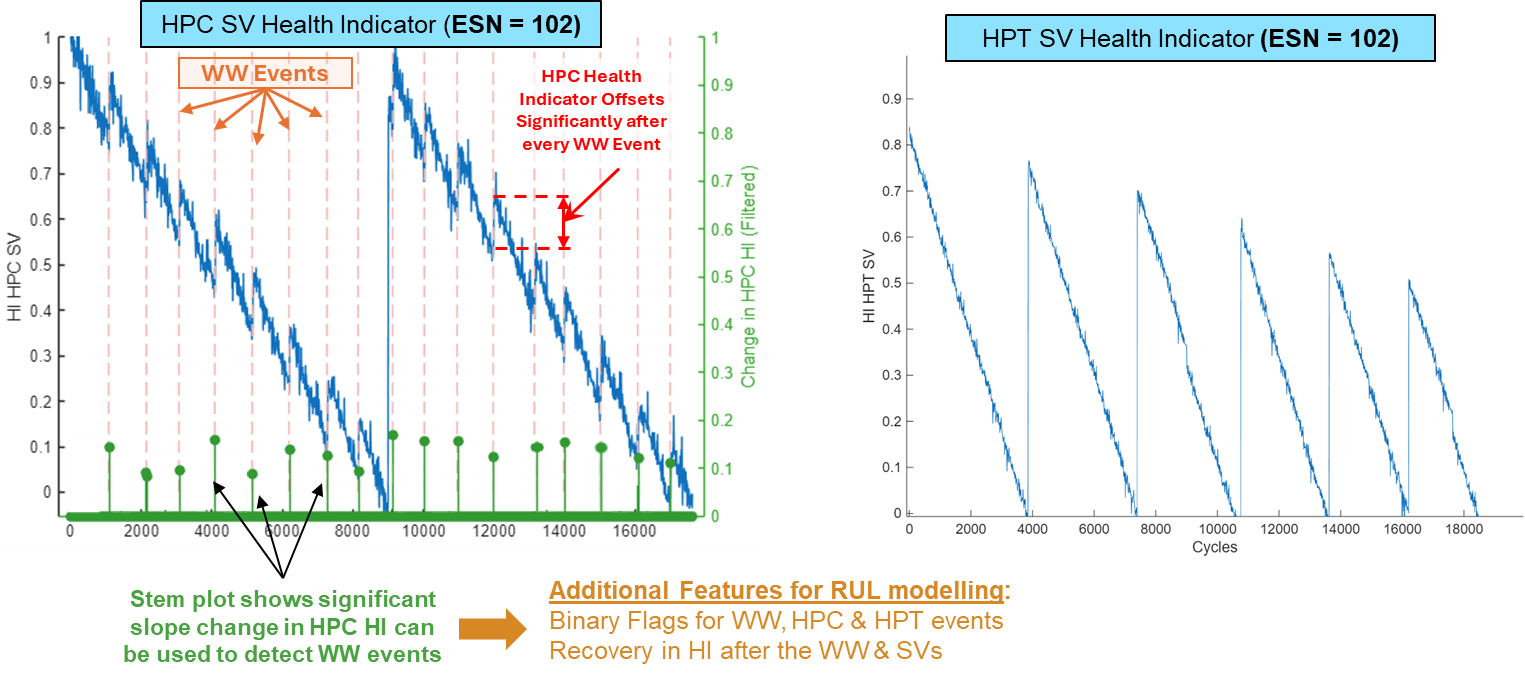

Remaining Useful Life features such as event flags and post-event Health Indicator recovery metrics.

评论

要发表评论,请点击 此处 登录到您的 MathWorks 帐户或创建一个新帐户。