Modeling Starts With the Question – On model fidelity, abstraction, and engineering judgement

Guest Blogger

George Amarantidis Koronaios is a Developer Advocate at MathWorks. He focuses on technical engagement with the engineering community, with an emphasis on Design Automation workflows and control systems. He actively engages with users serving as a bridge between practicing engineers, researchers, and product development teams. His work revolves around translating real-world engineering challenges into practical modelling and simulation workflows.

===

When we talk about model fidelity, we are often referring to different things without realizing it. Fidelity might describe geometric detail, physical realism, sensor modeling, or numerical accuracy, depending on the context.

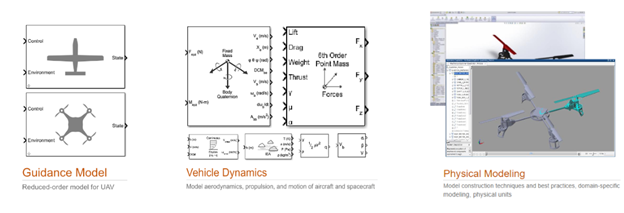

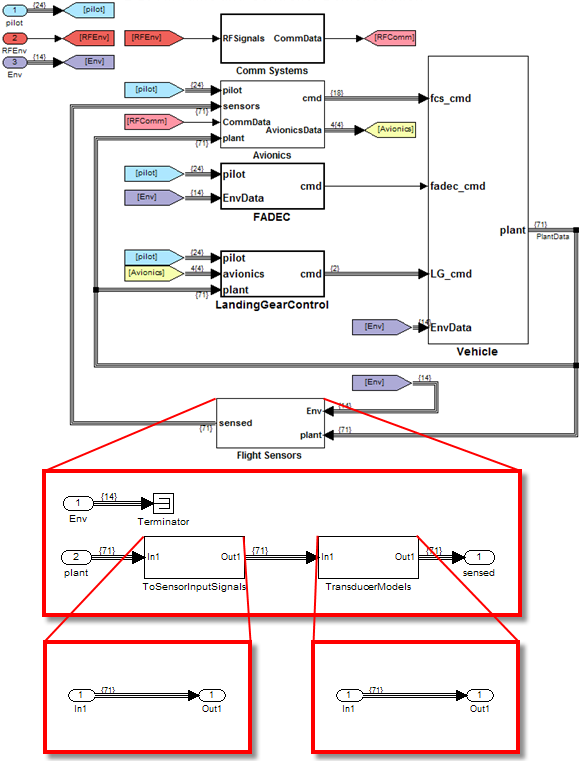

In a UAV setting, you might choose to model the vehicle as a simple point moving in three-dimensional space, or as a full rigid-body system with attitude dynamics. Sensors may be treated as ideal signals, or modelled explicitly with noise, bias, and failure modes, and the underlying physics may be represented using simplified equations or first-principles physical modelling.

Which of these choices makes sense depends on what we are trying to understand. When exploring guidance logic, waypoint sequencing, or high-level control structure, a point-mass representation may be entirely sufficient. When actuator limits, aerodynamic coupling, or energy constraints become central to the problem, a full vehicle dynamics model is often necessary. In practice, both approaches can be appropriate, the difference lies not in their “quality,” but in the questions they are designed to answer. This way of working – choosing the level of detail based on the question being asked, and evolving models as those questions change- is central to model-based design and critical to many modern engineering workflows.

Start With a Question, Not a Model

Many modeling challenges stem from a simple mismatch: the fidelity of the model does not align with the decision it is meant to support.

This becomes particularly clear in autonomy and UAV modeling. A common early goal might be to make a vehicle hover, track a simple reference, or follow a waypoint. At this stage, the primary questions are whether the control structure behaves sensibly, whether the signals are defined correctly, and whether the closed loop is stable. These questions can often be answered using relatively simple models that assume ideal actuation and abstract away much of the underlying physics.

Introducing detailed aerodynamics, actuator dynamics, or sensor fusion at this point rarely adds insight. More often, it obscures the basic behavior the engineer is trying to understand.

As the work progresses, however, the questions naturally evolve. Attention shifts to the effect of sensor noise, bias, or loss; to the behavior of estimators when absolute measurements (such as GNSS) are removed; or to how different subsystems interact across domains. At that point, the original low-fidelity model is no longer sufficient. Increasing fidelity becomes necessary; not because the earlier model was “wrong,” but because the question has changed.

Fidelity Is a Trajectory, Not a Single Choice

Model fidelity is often discussed as a binary choice: low versus high. In practice, it is more useful to think of fidelity as something that evolves over time.

In a UAV context, an early guidance-level model may treat the vehicle as responding exactly as commanded. This abstraction allows us to focus on guidance logic and control structure without being distracted by implementation detail. As confidence grows, additional fidelity can be introduced to study estimation behavior, sensor noise, or the consequences of disabling a measurement source. Later still, higher fidelity may be required to evaluate robustness to disturbances, actuator limits, or environmental effects.

As a matter of fact, when designing complex systems, large scale models will have parts of higher fidelity and parts of lower fidelity being interchanged based on what questions we are trying to answer. Navigation may be modelled in detail while the vehicle dynamics remain simplified, or vice versa. What matters is not uniform realism, but alignment between fidelity and intent.

When “Unrealistic” Models Are Still Useful

A common concern I hear is that low-fidelity models can be misleading because they are not realistic. This can be true… but only if realism is the goal.

In early UAV studies, models are often used to demonstrate mechanisms rather than to make precise predictions. For example, an inertial navigation solution may be configured to show how position error drifts when GNSS is disabled. The exact rate of drift may not yet be realistic, but the model clearly illustrates the underlying behavior: without absolute measurements, errors accumulate. A model that clearly demonstrates drift, noise amplification, or loss of observability can be valuable even if it is not yet calibrated to real-world data.

Similarly, comparing noisy sensor outputs with a true state can reveal how estimation uncertainty propagates through the control loop. Observing how a controller responds to degraded sensing often provides more insight than a numerically accurate but opaque simulation.

Low-fidelity models often rely on abstraction. This is sometimes interpreted as “hiding” important dynamics. More accurately, abstraction is a way of isolating the aspect of the system currently under study.

This philosophy is reflected in guidance-level UAV models, which intentionally assume that the vehicle responds exactly as commanded. The aim is not to deny the existence of actuator dynamics or low-level control, but to separate concerns. By abstracting the plant, these models allow engineers to study guidance logic, estimation quality, and information flow without conflating them with implementation detail. Actuator dynamics and environmental effects can be introduced later, once those questions have been answered.

Increase Fidelity When Uncertainty Becomes the Focus.

A useful guideline is to increase model fidelity when uncertainty itself becomes the quantity of interest. An example of this could be introducing sensor models (GPS, IMU) when studying estimation performance, or modelling actuator dynamics when evaluating implementation limits. At each stage, the added complexity should be justified by a specific question the model is meant to address.

Starting from High-Fidelity Models Can Be Unforgiving

High fidelity models come with a cost. Cost of computation, interpretability, and implementation. They are also less tolerant of poorly defined assumptions; inconsistent signal definitions; unclear modelling intent.

In UAV modelling, jumping directly to a fully coupled, sensor-rich, high-fidelity simulation can make it difficult to diagnose even simple issues. The model becomes harder to interpret at exactly the point when understanding is still forming.

High fidelity is most effective once the system behavior is already well understood at lower levels.

A More Useful Question

Rather than asking “is my model realistic enough?”, it’s often more productive to ask

- What problem am I trying to solve?

- What should my model include to support my engineering decisions?

Choosing the right level of fidelity at the right time is less about ideology and more about engineering judgement – and that judgement improves when models are built with intent.

댓글

댓글을 남기려면 링크 를 클릭하여 MathWorks 계정에 로그인하거나 계정을 새로 만드십시오.