DD ROBOCON India 2025 MathWorks Modeling Award: From Simulation to the Real-World with BRACT’s VIT Pune

In today’s blog, we have Tanmay Bora and Saumitra Kulkarni from Team BRACT’s Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, India. The team won the MathWorks Modeling Award at the DD ROBOCON India 2025 competition. Over to you..

Abstract

This blog highlights Team BRACT’s VIT Pune’s journey to a personal best finish of All India Rank 3 at DD ROBOCON India 2025, and how MathWorks tools enabled to transition their robots from simulation to reality. The blog covers their use of model-based design in Simulink and Simscape, image processing and computer vision workflows with the Computer Vision Toolbox and Deep Learning Toolbox, and a custom MATLAB App Designer-based interface for monitoring performance of their robots. The blog concludes with their key learnings from the competition and experience with MathWorks tools.

Motivation and Objective

The Team participated in DD ROBOCON India 2025 to enhance their robotics skills by solving real-world engineering challenges. By using MathWorks tools to model, analyze, and optimize robot performance in dynamic environments, they aimed to surpass their previous quarterfinal finishes at this competition.

Problem statement for DD ROBOCON India 2025

At DD ROBOCON India 2025, each student team deployed two robots to compete in a fast-paced basketball match that emphasized both offensive and defensive strategies in a two-minute game with a 20-second shot clock. One robot specialized in scoring baskets, while the other focused on defense. As is required in a game of basketball, agility, strategy and precision, were key attributes demanded in the robots.

GIF 1: BRACT’s VIT Pune (in red) scoring a three-pointer on their way to the semi-finals.

GIF 2: BRACT’s VIT Pune (in red) demonstrating precise dribbling and agile movement across the court.

Approach

The Team simulated and tested prototypes of their robots in Simulink and Simscape to analyze mechanical design and control strategies. Canonical camera-based depth estimation and deep-learning based object-detection workflows, implemented with the Image Processing Toolbox , Computer Vision Toolbox, and Deep Learning Toolbox, facilitated real-time detection of the basketball and hoop to assist shots. ROS nodes, integrated using the ROS Toolbox, established a middleware that resulted in agile and semi-autonomous robot performance on the court.

(A) Hardware

Dribble:

GIF 3: The ball-dribbling mechanism designed and tested in Simscape (left) translated well into the real-world (right).

A pneumatically driven piston was engineered to deliver quick, controlled, and consistent basketball dribbles, with a motorized catching-system for ball retrieval. Back-of-the-envelope component sizing was optimized using MATLAB scripts and Simscape Multibody simulations, accelerating the development of this physical mechanism.

Throw:

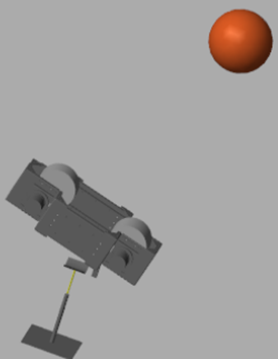

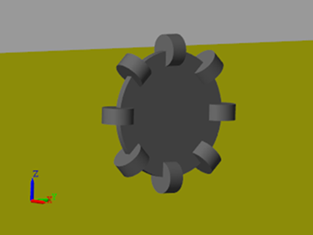

Figure 1: An electric motor-driven double-rotor mechanism conceptualized for the mechanism that shoots a basketball into a hoop.

An electric motor-driven shooter with counter-rotating rotors compressed the basketball before launching it. For a given distance from the hoop, height of the hoop, angle of launch of the ball, and mass of the ball, repeated tests in simulations using the Multibody Explorer of Simscape narrowed down the candidate launch velocities, forces of ball-compression, angles of launch, and motor RPMs, for this mechanism.

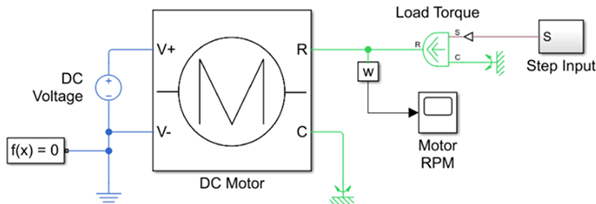

Figure 2: The Simscape™ model of an electric motor sketched by the Team.

The electric motors were modelled in Simscape and tested over a series of load torques – applied as step inputs – to simulate launch commands. Metrics such as RPM, current, and power, were monitored. The MY6812 DC motor was selected for its high torque and reliability, and its integration into the double-rotor mechanism enabled consistent launch velocities. Motor RPM was empirically mapped to robot position relative to the hoop and regulated by a PID controller tuned using the Zeigler-Nichols method.

GIF 4: A well-tuned electric motor-driven double-rotor mechanism shoots a basketball into the hoop in a Simscape simulation (left) and in the real-world (right).

Defense:

GIF 5: A belt-and-pulley driven net blocked and defended against the opponents’ shots at the hoop, in simulation (left) as well as in the real-world (right).

A motor-driven belt-and-pulley system deployed a flexible net on the second robot to block opponent shots. The net was modelled in Simscape with spring-damper properties to replicate realistic energy absorption. A 555 PMDC motor actuated and stabilized the defense mechanism against load-torque variations during a block.

Motion:

Figure 3: Omni-directional wheels modeled in Simscape (left) were arranged at 120-degree intervals on the robot base (right).

Three motor-driven omnidirectional wheels enabled agile and holonomic movement for both robots. Each wheel was modeled in Simscape with disks and perpendicular rollers that realistically simulated wheel-ground interactions.

(B) Software

Detecting the basketball and hoop:

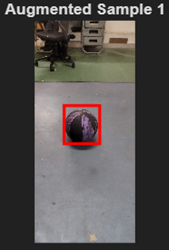

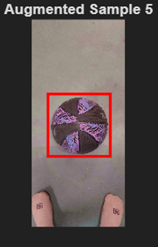

Figure 4: Detecting basketballs (top) and hoops (bottom) from different point-of-views in images using a MATLAB-OpenCV-YOLOv4 pipeline.

A computer vision pipeline in MATLAB, with OpenCV integrated, was used to detect the basketball and hoop in real-time. This detection was the first step to predict the trajectory of the ball for an attempted shot from a given position on the court and provided real-time feedback to the student operator to correctly position the robot before taking a shot.

Preparing the dataset – The Image Labeler application in the Computer Vision Toolbox was used for annotating a dataset of 1000 images of basketballs and hoops, collected from diverse point of views of the camera. Data-augmentation techniques such as horizontal flips, random colour jitter, scaling, and image cropping, were applied to the training samples for robustness against variations in lighting conditions, camera angles, and ball orientations, typically encountered during a match. Preprocessing techniques such as aspect ratio preservation and pixel scaling were applied to normalize images fed into a machine learning model for detecting basketballs and hoops. This improved convergence and reduced overfitting at the time of training the model.

Creating an object detection network – The yolov4ObjectDetector MATLAB function was used to create the YOLOv4 one-stage object detector provided in the Deep Learning Toolbox. Techniques such as Mosaic data augmentation, DropBlock regularization, and Self-Adversarial Training, available in the ‘Bag of Freebies’ in YOLOv4, improved object detection in different lighting conditions and noise levels, and reduced the size of the dataset required.

Training and evaluating the YOLOv4 object detector: An appropriate batch size, learning rate, and number of epochs, were provided to train the YOLOv4 one-stage object detector after splitting the dataset for training (60%), validation (10%) and testing (30%). The average precision metric and the precision-recall curve generated in the Deep Learning Toolbox were used to evaluate the accuracy of the object detector. Over the course of training, an average precision of 0.97 and 0.95 was achieved for the hoop and basketball, respectively.

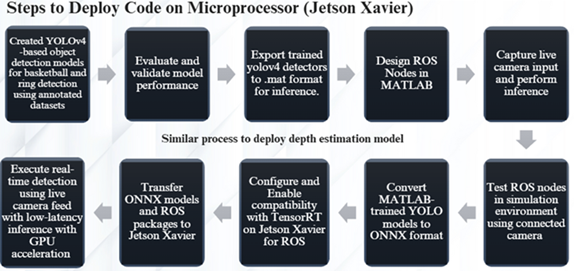

Deployment on Jetson Xavier with ROS integration:

Figure 5: The workflow used to deploy the YOLOv4-based object detection models on an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier computer.

The flowchart shown above outlines the workflow used to deploy the YOLOv4-based object detection model on an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier computer. The detector was launched on the computer by converting MATLAB-trained models into an ONNX format, optimized using TensorRT. These models were integrated into ROS nodes, developed in the ROS Toolbox, and transferred to the Jetson Xavier, where GPU acceleration enabled fast, reliable detection and trajectory estimation from live mobile video feeds on the robot.

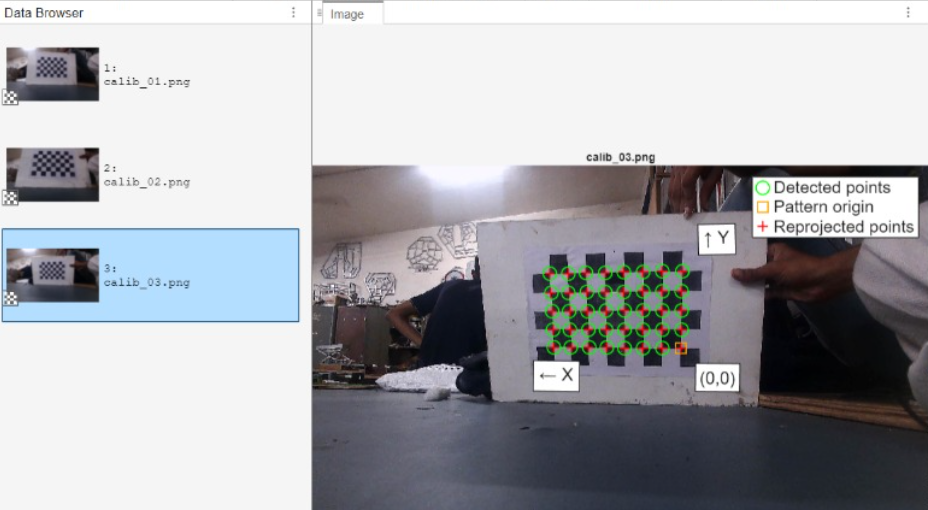

Camera Calibration:

Figure 6: Using a checkerboard pattern to calibrate cameras for depth-estimation.

The Team installed camera-equipped mobile phones on the robots. Camera-calibration was performed using a checkerboard pattern to accurately map object-detections from image space to real-world coordinates. The estimateCameraParameters MATLAB function of the Computer Vision Toolbox estimated both intrinsic and extrinsic parameters and corrected for lens distortion. Calibration helped relate the basketball and hoop in a 2D image to their 3D location relative to the robot on the basketball court.

Using ArUco Markers to estimate distance from the hoop:

Figure 7: Using an ArUco marker to estimate real-time position and orientation of the robot relative to the basketball hoop.

The calibrated mobile phone camera was used with an ArUco marker to estimate the real-time position and orientation of the robot relative to the basketball hoop. The Team positioned the marker on a flat surface close to the hoop during the pre-match setup window offered to students. The readArucoMarker MATLAB function was used to detect the marker in a live video stream from the mobile phone. Therefore, during a match, the team could estimate the distance and heading of the robot relative to the hoop, and command motor RPMs if needed, before taking a shot to score a basket. In autonomous mode, the position and orientation data would be relayed to an internal PID based control system that pointed the robot at the hoop.

Estimating trajectory of the basketball:

Figure 8: Tracking the position and velocity vector of the center of the basketball.

The center-pixel of the ball was tracked over multiple image frames to predict its velocity and future trajectory. This capability allowed the student operator to judge, in real time, if the ball would pass through the hoop, and aided in manually adjusting the pose of the robot, and the motor RPMs of the shooting mechanism.

Real-time performance monitoring on a GUI:

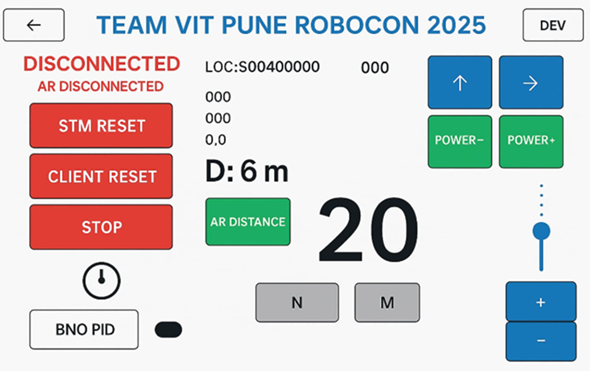

Figure 9: A graphical user interface developed in the MATLAB App Designer to monitor robot health.

A live video-stream, overlaid with the detections of the basketball and hoop, was relayed to a graphical user interface (GUI) that displayed on screens fit onto remote controllers used by the students to control the robot. This GUI was developed using the MATLAB App Designer. In addition to the object detections, the GUI also displayed the estimated distance of the robot to the hoop, the anticipated trajectory of the basketball before a shot was taken, and data to monitor system health.

Results

At the DD ROBOCON India 2025 competition, the team achieved an All India Rank 3 and brought home the MathWorks Modelling Award, the NAM:TECH Award for Second Runner-Up, and the IHFC Award for Robotics and AI. These honors recognized their innovation and technical skill, highlighting the importance of simulations and mathematical modeling in robotics. The Team leveraged a model-based design workflow to evaluate multiple concepts, fine-tune mechanisms, and eventually finalize designs that were both practical and competition-ready.

Learning

The key positives observed by the team can be summarized as

1) Model-based design and simulations allow a system to be virtually tested, optimized, and verified, before being fabricated. This saves time, effort, and resources

2) Building and deploying a robot to solve real-world engineering problems provides exposure to skills spanning mechanical design, electrical systems and circuits, computer engineering, computer science, optics, sensor integration, and fabrication .

Next Steps

Looking ahead, the Team plans to build on their present work by

1) using the PID Tuner app for automatic tuning of the PIDs that control motor RPMs, and

2) using the Reinforcement Learning Toolbox from MathWorks to train the robots in adversarial scenarios and improve high-level decision making in dynamic environments (for e.g., to shoot a basket or pass the ball?).

댓글

댓글을 남기려면 링크 를 클릭하여 MathWorks 계정에 로그인하거나 계정을 새로 만드십시오.