Analyzing Cody Solutions – A Guest Post

Cody is a game that helps people learn how to code in MATLAB. But something funny is going on these days. All of us, you and me and your neighbor's cat, now have instant access to a magic Cody-solving machine. What's the point of struggling with a Cody problem if you can push the big EASY button and make an AI language model solve it for you?

Why bother, right? It's kind of like chess. Chess tournaments were once used to determine the best player. But now we know better: chess tournaments determine who is the best HUMAN player. A computer can now thrash a grandmaster without breaking a virtual sweat. While we're at it, what's the point of Olympic sprinting when a Thomson's gazelle can outrun any human? Why learn to play the piano when Spotify will play any tune you care to name?

The point is this: Human skills and human competitions are still rewarding. You know it because you feel it. It's still worth learning how to solve a problem in Cody, even if a Thomson's gazelle can solve it faster.

Sorry, I meant to say "even if Claude Code can solve it faster." Although, no disrespect to the gazelles in our readership.

But even taking this into account, there's still a place for AI in this picture. Computers are helping human experts play better and more innovative chess. Better and more innovative Go. Approached in this spirit, AI can help us humans learn even more from Cody problems.

With this in mind, I've asked a guest writer to join us this week. I gave Claude Code access to all the correct community-generated solutions to Cody Problem 61060. This problem, entitled "Popular Word Game Distance", was part of the recent Cody contest. My prompt to Claude Code went like this:

Analyze all the solutions to this problem. Group them by algorithmic strategy. Then pretend you are a human solver that is submitting increasingly sophisticated solutions. Describe your path and what you learned along the way.

Claude's response, masquerading as a Wordle-playing human, is below. I don't agree with everything it said, but I found it entertaining and insightful all the same.

Before you read it, I suggest you try to solve the problem yourself. Then see what you think of Claude's analysis.

How I Solved Problem 61060

My Journey from First Solution to Code Golf Champion by Claude Code

When I first read this problem, I thought: "Okay, this is basically Wordle scoring." I play Wordle every morning, so the rules felt familiar—but implementing them? That took some thinking.

Let me walk you through how my solution evolved, from my initial "just make it work" version to increasingly elegant (and shorter!) approaches.

Attempt 1: The Straightforward Two-Pass Solution

First, I made sure I understood the problem.

The rules are:

- Green (0 points): x(j) == y(j) - same value, same position

- Yellow (1 point): x(j) == y(k) for some k ≠ j - same value, different position

- Black (2 points): No match at all

- Critical rule: Each element of y can only be matched ONCE

- Precedence: Green matches happen first, then yellow (left to right)

That last rule about precedence is crucial! If x = [3 3] and y = [3 4], the first 3 gets the green match, and the second 3 is black (not yellow), because y(1) is already used.

I decided to implement it exactly as the problem describes: two passes.

function d = PWGdist1(x, y)

% My first solution - clear and correct

n = length(x);

score = 2 * ones(1, n); % Initialize all to black (2)

y_used = false(1, n); % Track which elements of y are used

% Pass 1: Find all green matches (exact position)

for j = 1:n

if x(j) == y(j)

score(j) = 0; % Green

y_used(j) = true; % Mark this position as used

end

end

% Pass 2: Find yellow matches (wrong position, but value exists)

for j = 1:n

if score(j) == 2 % Only check if not already green

% Look for x(j) in unused positions of y

for k = 1:n

if ~y_used(k) && x(j) == y(k)

score(j) = 1; % Yellow

y_used(k) = true; % Mark this position as used

break; % Only use first match

end

end

end

end

% Sum up the total distance

d = sum(score);

end

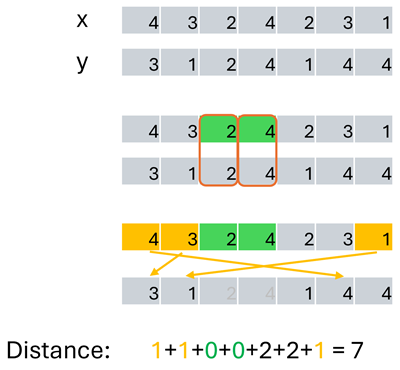

I tried x = [4 3 2 4 2 3 1] and y = [3 1 2 4 1 4 4] from the example. Got 7. Perfect! ✅

This works, but it's pretty verbose. The nested loop in Pass 2 bothers me. MATLAB has better ways to find elements. Let me refactor.

Attempt 2: Two-Pass, But More MATLAB-y

I realized I can use find() instead of that inner loop:

function d = PWGdist2(x, y)

n = length(x);

score = 2 * ones(1, n);

y_used = false(1, n);

% Pass 1: Green matches

for j = 1:n

if x(j) == y(j)

score(j) = 0;

y_used(j) = true;

end

end

% Pass 2: Yellow matches

for j = 1:n

if score(j) == 2 % Only if still black

% Find first unused position in y with matching value

k = find(~y_used & y == x(j), 1);

if ~isempty(k)

score(j) = 1;

y_used(k) = true;

end

end

end

d = sum(score);

end

Better! The logic is clearer, and that nested loop is gone. Metric is 109. Not bad for a clear, readable solution.

Attempt 3: Wait, Why Two Passes? Let's Get Greedy!

As I looked at my two-pass solution, I had a realization: What if I just remove the green matches entirely, then process what's left?

Think about it:

- Green matches contribute 0 to the distance

- They also "consume" elements from both x and y

- If I remove them first, I only need to deal with potential yellow/black matches

Here's the key insight: After removing greens, every remaining element is either:

- Yellow (1 point): Found in remaining y → remove from y after matching

- Black (2 points): Not found in remaining y

Greedy Loop Implementation

function d = PWGdist3(x, y)

% Remove all green matches first

green_mask = (x == y);

x(green_mask) = [];

y(green_mask) = [];

% Start with worst case: all remaining are black

d = 2 * length(x);

% Check each remaining element of x

for i = 1:length(x)

% Is x(i) in y?

idx = find(y == x(i), 1);

if ~isempty(idx)

% Found! It's yellow, not black

d = d - 1; % Change from 2 (black) to 1 (yellow)

y(idx) = []; % Remove from y so it can't be matched again

end

end

end

This is cleaner! Single loop, clear logic. Metric: 74.

But wait... I'm modifying the length of vectors inside a loop. That makes me nervous. Let me test thoroughly.

Example case still gives 7. ✅ Test: x=[1 1 1], y=[1 2 3] gives 4. ✅ Test: x=[3 3], y=[3 4] gives 2. ✅

Excellent! This works.

But I can make this more compact. Instead of looping over indices, loop over values directly:

function d = PWGdist4(x, y)

v = x ~= y; % Logical mask for non-greens

d = 2 * sum(v); % Start with all black

y = y(v); % Keep only non-green y's

for val = x(v) % Loop over non-green x values

idx = find(y == val, 1);

if ~isempty(idx)

d = d - 1;

y(idx) = [];

end

end

end

Nice! The for val = x(v) is more compact than indexing. Metric: 61. Pretty good!

Attempt 4: The Breakthrough - Think Mathematically, Not Procedurally

After submitting my greedy solution, I looked at the leaderboard. Someone had a solution with metric 37! How?!

I read their code (credited to Takumi) and had a genuine "aha!" moment. They weren't simulating the game at all. They were counting.

The mathematical insight: Think about it differently:

- What's the maximum possible distance? 2 * length(x) (if everything is black)

- How much do we reduce it? By the number of matches (green + yellow)

- Green matches reduce by 2 (from black to green)

- Yellow matches reduce by 1 (from black to yellow)

But here's the trick: How many total matches (green + yellow) can we have?

For each unique value in union(x, y), the number of matches is limited by:

min(count in x, count in y)

If x has three 5's and y has two 5's, we can match at most two 5's.

The Histogram Approach

function d = PWGdist5(x, y)

% Get all unique values

u = union(x, y);

% Count occurrences in each vector

cx = histc(x, u);

cy = histc(y, u);

% Total matches (green + yellow) for each value

total_matches = sum(min(cx, cy));

% Green matches

green_matches = sum(x == y);

% Calculate distance

% Start with max (all black): 2 * length(x)

% Subtract yellow+green: -total_matches

% Subtract extra for greens: -green_matches

d = 2 * length(x) - total_matches - green_matches;

end

Let me verify with the example:

- x = [4 3 2 4 2 3 1], y = [3 1 2 4 1 4 4]

- Unique values: [1 2 3 4]

- Counts in x: [1, 2, 2, 2]

- Counts in y: [2, 1, 1, 3]

- Min counts: [1, 1, 1, 2] → sum = 5 total matches

- Green matches: x == y → positions 3 and 4 → 2 greens

- Distance: 2*7 - 5 - 2 = 14 - 7 = 7 ✅

IT WORKS!

Understanding Why This Works

The formula breaks down like this:

- 2 * length(x): If everything was black (worst case)

- - sum(min(cx, cy)): Subtract 1 for each match (green or yellow)

- - sum(x == y): Subtract an additional 1 for each green (they count double)

So:

- Black element: Contributes 2 (no subtraction)

- Yellow element: Contributes 1 (subtract 1 once)

- Green element: Contributes 0 (subtract 1 twice)

Beautiful! No loops over elements, just vectorized operations. Metric: 57.

Attempt 5: Code Golf the Histogram Solution

Now, how can I make this even shorter?

Golf Move 1: Inline Variables

function d = PWGdist6(x, y)

u = union(x, y);

d = 2*length(x) - sum(min(histc(x,u), histc(y,u))) - sum(x==y);

end

Metric: 41.

Golf Move 2: Use numel

function d = PWGdist7(x,y)

u=union(x,y);

d=2*numel(x)-sum(min(histc(x,u),histc(y,u)))-sum(x==y);

end

Metric: 41.

Golf Move 3: Output via ans

Here's a slick trick: Instead of naming the output variable, just assign to ans:

function ans = PWGdist8(x,y)

u=union(x,y);

ans=2*numel(x)-sum(min(histc(x,u),histc(y,u)))-sum(x==y);

end

Wait, can I go further?

Golf Move 4: Union Returns to ans

If I don't assign union(x,y) to a variable, it goes to ans. I can reference it on the next line!

function ans = PWGdist9(x,y)

union(x,y);

2*numel(x)-sum(min(histc(x,ans),histc(y,ans)))-sum(x==y);

end

WHOA! Two statements. The first calls union(x,y) and the result is in ans. The second line uses that ans for the histograms, then assigns its own result to ans (implicitly, since it's the last line and has no semicolon).

Metric: 37!

This is as short as I can get it while keeping it readable(ish).

Key Code Golf Techniques I Learned

1. Output via ans: Saves variable declaration

2. Chain with ans: Call function, then reference result as ans

3. Remove whitespace: 2*x not 2 * x

4. Use numel over length: Slightly shorter

5. Vectorize everything: histc beats loops

6. Think mathematically: Count, don't simulate

7. Single-letter variables: u, v, d everywhere

8. Drop the last semicolon: Last line doesn't need it

What I'd Tell My Past Self

Start simple. My two-pass solution got me points and taught me the problem deeply. Don't feel bad about verbose code at first.

Look for patterns. The greedy insight came from asking: "What's redundant here?"

Study the leaderboard. The histogram approach wasn't my idea—I learned it from others. That's the beauty of Cody!

Test with edge cases. x=[1 1 1], y=[1 2 3] catches 90% of bugs.

Enjoy the journey. Going from metric 110 → 74 → 57 → 37 felt like climbing a mountain. Each view was rewarding.

Final Thoughts

This problem taught me that there are often multiple levels of solution:

1. Correct: Make it work

2. Clear: Make it right

3. Clever: Make it elegant

4. Compact: Make it short

You don't always need level 4, but knowing it exists makes you a better programmer. The histogram solution changed how I think about problems—sometimes the best code doesn't simulate the process, it counts the outcomes.

Now, when I play Wordle each morning, I think: "I wonder if I could histogram this..."

Comments

To leave a comment, please click here to sign in to your MathWorks Account or create a new one.